History of Austin

Here's the history behind Austin's most famous tree — legendary Treaty Oak

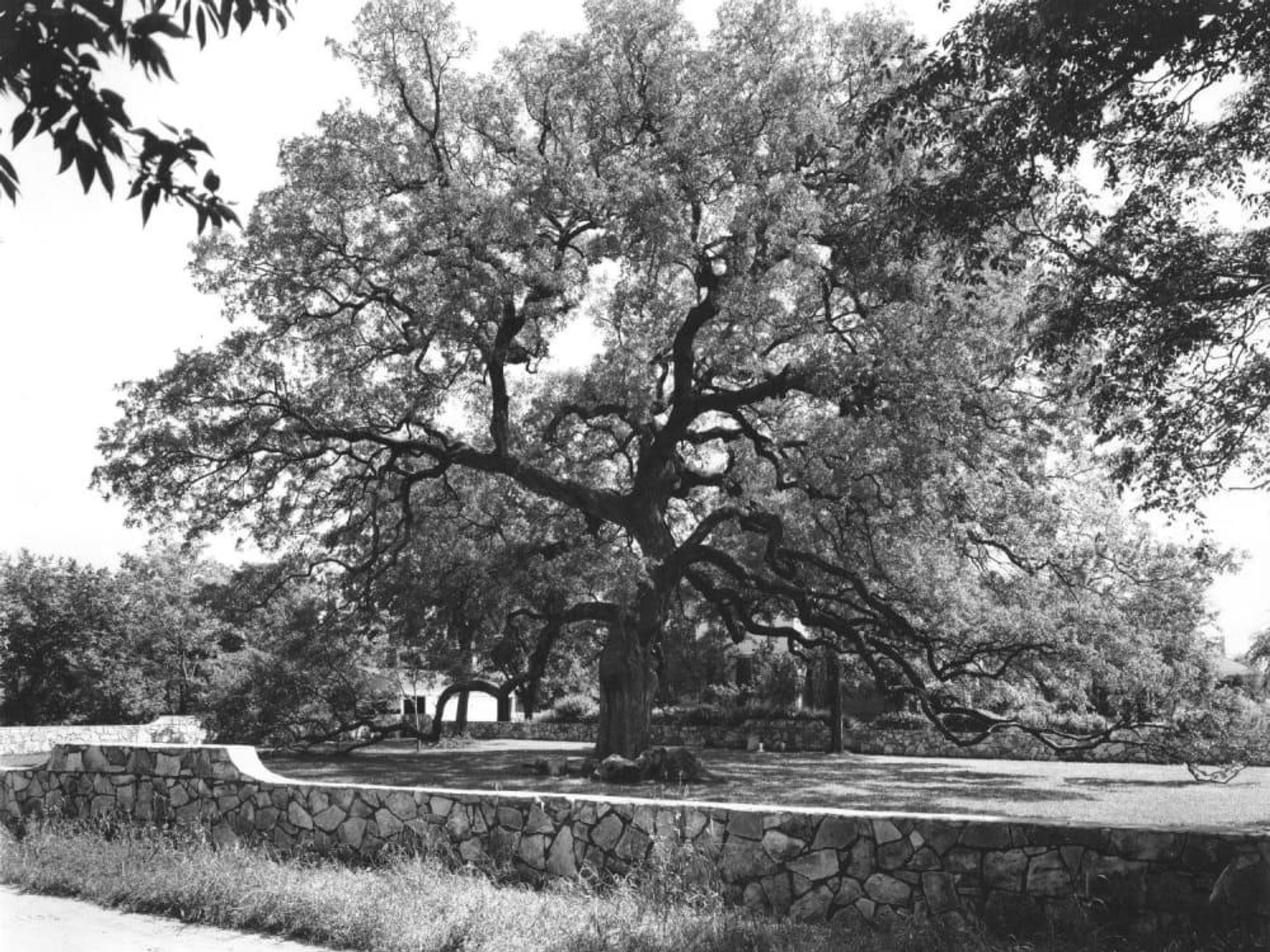

Majestically standing on a small downtown lot on Baylor Street, sandwiched between Fifth and Sixth streets, is a Southern live oak tree known as Treaty Oak. The tree is the only surviving member of the original 14 Council Oak trees that bore witness to meetings between Tonkawa and Comanche tribe members and the father of Texas, Stephen F. Austin.

Legend has it that leaves of Treaty Oak, along with acorns from the tree, were brewed into tea by females of Native American tribes to promote the safe return when warriors returned from battle. The tea was also brewed as part of a superstitious belief promoting fidelity in unions among members of the tribe. Beneath the limbs of the Council Oaks, dances were performed, war councils commenced, conferences were held, and pacts and treaties were signed. It is also said that Sam Houston contemplated his future under the shade of the oak tree after he was ousted as the governor of Texas.

Treaty Oak, the last remaining tree of the Council Oaks, obtained national status as the most perfect example of a North American tree and was entered into the National Forestry's Hall of Fame in 1927. During a period in the late 19th century, Treaty Oak was privately owned by a local family. The City of Austin purchased the tree for $1,000 in 1927. The tree is accessible to the public, and there is a plaque summarizing the history of Treaty Oak on the Baylor property.

Modern-day poisoning

March 2, 1989, typically a day of celebration as it is Texas Independence Day, became a day that Austinites recall with sorrow. It was the day when a group of people gathering around Treaty Oak for a tree meeting noticed dead grass and sick leaves on and around the base of the tree. Initially it was assumed that a city worker had been negligent and applied too much chemical to the tree, but after subsequent observation and testing, it was revealed that the tree had been intentionally poisoned with the herbicide Velpar.

In fact, enough Velpar was used to kill 100 trees. Austinites rallied in outrage; groups gathered to hug the tree and ward off evil spirits; and, most beneficial, a blank was check written by Ross Perot, along with a $10,000 reward offered by DuPont, the manufacturer of Velpar.

No lead was too small to follow, but ultimately the vandal, Paul Cullen, was identified after telling friends that he had poisoned the tree to "cast a spell" to kill his unrequited love for a counselor he met at a methadone clinic. Local and statewide news teams followed the story on a daily basis, vigils were held, yellow ribbons were placed around the tree, and children wrote get-well letters for the tree. Psychics descended on the city and chanted a "transference of energy," hoping the tree would shed its toxins and begin to heal.

Paul Cullen eventually served a nine-year prison sentence for his act. Cullen died in 2001 at the age of 57.

A Treaty Oak Task Force made up of local and national arbor professionals was formed to identify strategies to save the beloved piece of Austin history. Michael Embesi, community tree preservation manager with the City of Austin, was a student in Austin when Treaty Oak was poisoned and remembers the community rallying together to save this iconic piece of history.

Embesi has worked with the city tree program for 20 years and frequently consults with developers in incorporating trees into project designs satisfying all parties involved. He said our community passed the first tree protection ordinance in the country in 1983, and now there are literally thousands of similar programs across the country, 100 of these programs are in the state of Texas. And certainly Austin is growing rapidly, but Embesi believes that trees are part of the attraction for businesses when they decide to locate to Austin. "Trees are like us," Embesi adds, "they acclimate to their environment just as we do."

Most consulting arbor experts had predicted that Treaty Oak would not survive, and defying all odds Treaty Oak did survive. Moreover, in 1997 the tree began to produce acorns. Although approximately two-thirds of the tree did not recover from the incident, limbs were treated, some dead limbs were removed and made into products for fundraising, and saplings were sold and planted across the city as a reminder of the once majestic oak that stood as a testament to history and survivorship.

One of the best-known saplings is planted on the plaza of the grounds at Austin City Hall and stands as a witness to history. "Mighty oaks from little acorns grow" is more than just an expression, it is a way of life for many Austinites.