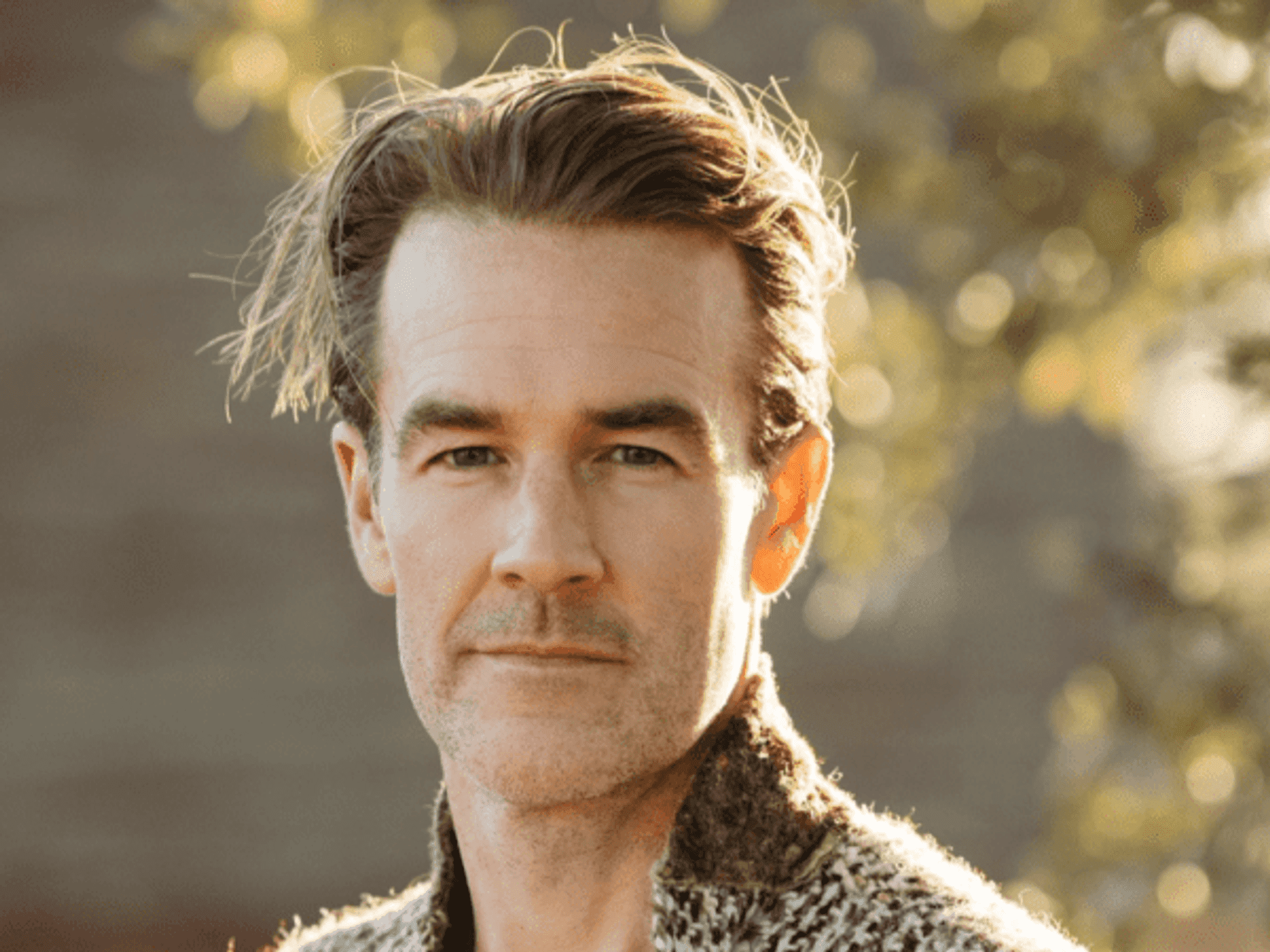

AustraPhoto by Bill Sallans

AustraPhoto by Bill Sallans AustraPhoto by Bill Sallans

AustraPhoto by Bill Sallans AustraPhoto by Bill Sallans

AustraPhoto by Bill Sallans

Katie Stelmanis' 2008 album Join Us matched her operatic voice with plaintive keys and glowing beats, a very arch and formal LP cut and paste from Kate Bush, Cabaret Voltaire, and classical music. That collage begged the question: Was this some sort of art school project, or was she serious? With new band Austra, the Toronto musician has a clearer vision of electronica.

A classically trained opera singer, Stelmanis uses her incredible vibrato to maximum effect, which can be a bit grating at times, but she definitely has control over it.

The fivepiece band, with linchpin drummer Maya Postepski, hit singles “Lose It” and “Beat and Pulse,” both from debut LP Feel It Break (Domino), Stelmanis' Stevie Nicks incantations and long tapestry kaftan adding to the witchy disco vibe.

“Lose It” sounds club-ready, an anthem for something and nothing; stylish and catchy, like something you'd hear in a Forever 21. Not all of Austra's jams were so anthemic, though—some were more intricate and melodramatic, synth and beat tumbling down repetitive Italo-disco inclines.

They lost some speed on the more ballad-y fare, but in this era of synth culture redux, they're at least trying to recontextualize it. The costumed backup singers (and twin sisters) harmonizing with Stelmanis gave the set a more primal feel, without the smeared mascara and ripped fishnets—electronic music expertly dug up through punk roots.