From experimental ceramics to multimedia installations incorporating found materials, Austin's early winter exhibitions showcase artists who are pushing the boundaries of their mediums while exploring themes of heritage, identity, and our relationship with nature.

Across seven venues, from the Blanton Museum to intimate gallery spaces like the Wally Workman Gallery, these exhibitions showcase both established and emerging artists. Their works invite viewers to experience familiar subjects through fresh perspectives, creating opportunities for both curiosity and education.

Dimmitt Contemporary

Michael Dines: Echoes of Tonalism — through December 13

Dines creates haunting works that transcend traditional landscape painting, using the natural world as a foundation for exploring deeper artistic elements. The artist creates a compelling tension between surface and depth, inviting viewers into mysterious, otherworldly scenes while simultaneously emphasizing their separation from these spaces. The resulting works feel like portals into an alternate reality, where familiar natural forms merge with abstract elements to create something entirely new.

Wally Workman Gallery

Will Klemm:Elevations — December 7-29

Klemm presents a collection of ethereal landscapes that capture nature's most evocative moments, from emerging sunsets to dusky forest scenes. A nationally recognized artist with more than 40 solo exhibitions across major U.S. cities, Klemm demonstrates his mastery of both pastel and oil in large-scale works that poetically interpret Southwestern landscapes from Texas to California.

Lora Reynolds Gallery

Tony Marsh: On the Clouds of Magellan — through January 1

Created over the past year, Marsh’s new sculptural works explore human torso forms and, for the first time in his career, wall-mounted pieces. The exhibition demonstrates his evolving approach to surface treatment, alternating between smooth and heavily textured surfaces, with experimental glazing techniques that include building with large chunks of glaze. Named after his father's poem about Magellan's explorations, the show marks a shift toward more personal and emotional expression in Marsh's work.

Blanton Museum of Art

Group Exhibition:Native America: In Translation — through January 5

This exhibition brings together nine Indigenous artists who explore contemporary Native identity through photography and multimedia works. The exhibition challenges historical photographic representations of Native Americans while presenting new narratives about Indigenous life today. Featured artists including Rebecca Belmore, Martine Gutierrez, and Kimowan Metchewais use various mediums — from Polaroids to video installations — to examine themes of memory, language, landscape, and beauty.

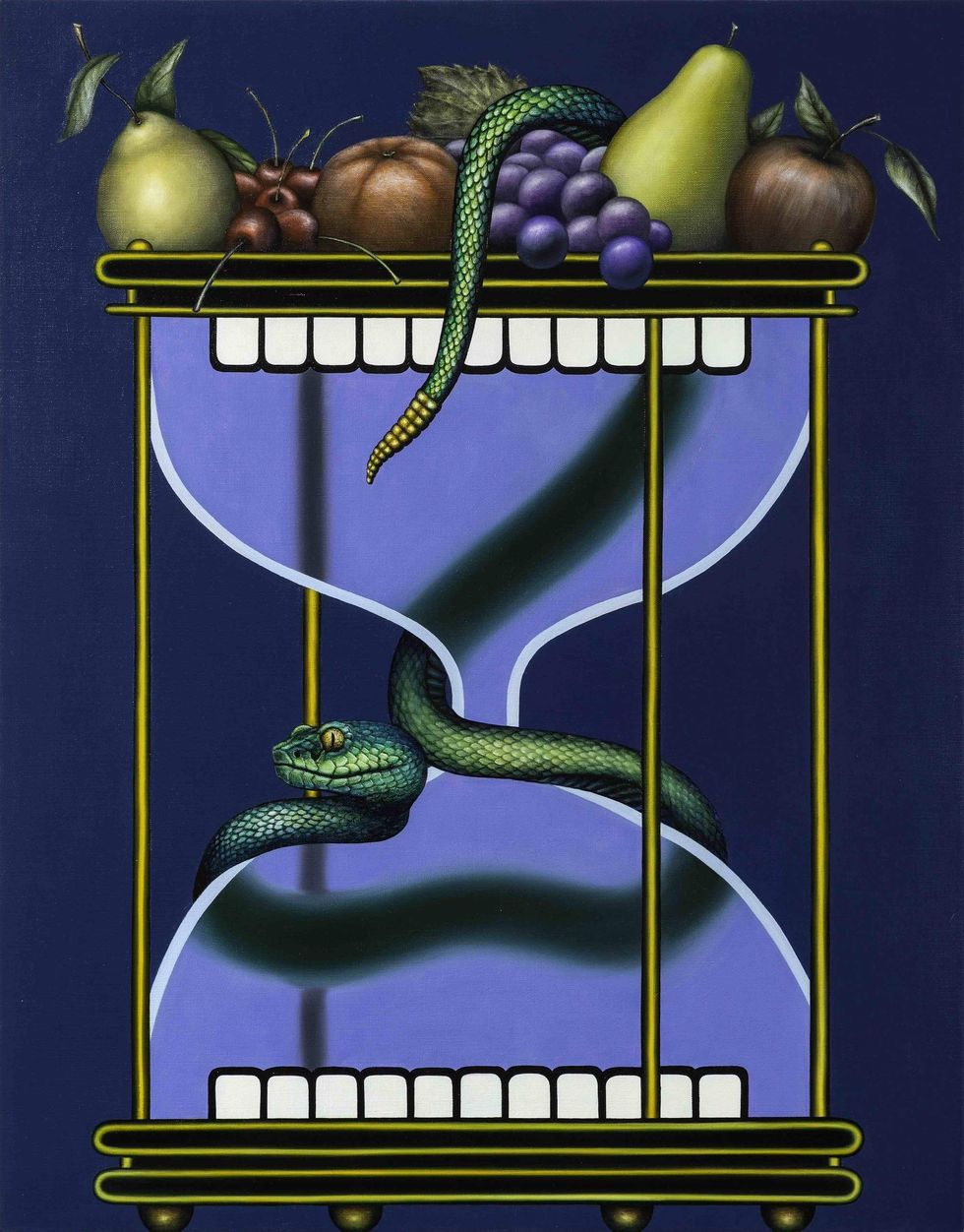

Group Exhibition: Long Live Surrealism! 1924-Today— through January 12

This multi-artist exhibition marks 100 years since Surrealism emerged as an artistic movement, changing modern perspectives by delving into dreams and the subconscious mind. The show includes pieces by key Surrealist figures such as Bellmer, Carrington, Ernst, Lam, and Ray, plus works by later artists like Kusama and Hood who were shaped by the movement's ideas.

Austin Public Library

Suzy González: Plantcestors — through January 12

González creates distinctive portraits that blend conventional oil painting with actual organic materials like pecans and seeds. Each work depicts members of local creative and social justice communities, with natural elements chosen to reflect each subject's background. The artist combines photography, gardening, gathering of materials, and preservation methods to produce layered compositions sealed in resin. These earth-toned works explore themes of cultural roots and heritage while physically incorporating elements from nature.

Davis Gallery

Group Exhibition: Breathe — through January 18

Davis Gallery’s 26th annual holiday show displays diverse works from 12 artists working across multiple mediums. The show features B Shawn Cox's vibrant acrylic paintings on fabric, which blend portraits with western themes, mixing feminine and masculine elements through unexpected color combinations and patterns. John Sager contributes mixed media assemblages crafted from found objects like printer's blocks, steel, and piano parts, while Lisa Beaman presents serene animal portraits depicting birds, rabbits, and cows in their natural settings.