Unrest in Austin

Austin's 3 days of turbulent downtown protests ignites citywide unrest

Editor's note: This past weekend, May 29 through May 31, cities across the U.S. saw large-scale protests in reaction to the death of Minneapolis resident George Floyd. In downtown Austin, thousands of demonstrators took to the streets for three days of protest that were at times peaceful, while others were violent. Below is an account of those protests.

Friday

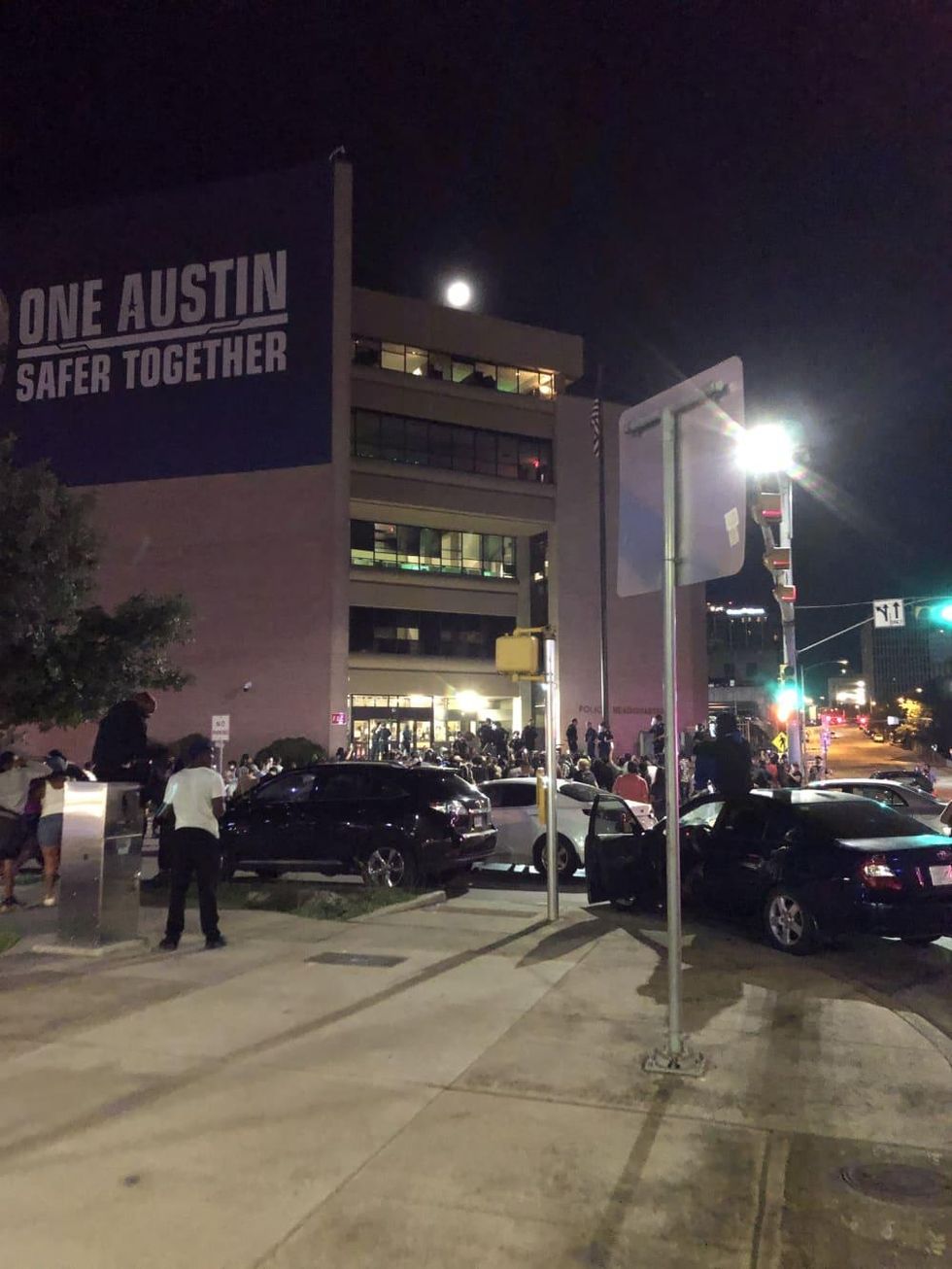

The unrest began after sunset on Friday, tipped off only by the buzz of a single helicopter circling around downtown. By midnight, about a hundred or so protestors had gathered outside the Austin Police Department’s Eighth Street headquarters, a nondescript, five-story building the same beige color of most government offices.

The demonstrators, a mix of Black, Hispanic, and white folks, had gathered on the corner of Eighth Street and the southbound I-35 Frontage Road to protest police brutality — namely the deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Michael Ramos in Austin. There were more phones than protest signs (this would change as the weekend continued) and more shouting than chants. The crowd, it seemed, skewed older, another thing that would shift over the next few days.

A wall of APD bicycle officers greeted the protestors, using their bikes as a blockade around the bottom steps of the headquarters. Behind them, colleagues were dressed in full riot gear with the exception of their boss, Chief Brian Manley, who darted around wearing only a blue face mask. If this was deliberate, it's unsurprising. Like his predecessor, Houston's current police chief Art Acevedo, Manley is PR savvy and likely understood the optics of a city seeing its chief in full riot gear.

Adding to the chaos was the area itself. Underneath the I-35 overpass is a parking lot turned homeless camp, so traipsing through the tents feels like trespassing. Though a few joined in, most residents just sat in their doorways, curiously observing the spectacle from their makeshift village.

As the early morning hours continued, the energy of the crowd began to swell. By 12:45 am, plastic water bottles, then glass beer bottles, were periodically chucked from the crowd at the officers. Police returned the favor with rounds of bean bag bullets, which when fired, sound remarkably, terrifyingly, like guns.

There was blood on both sides. Some reported that an officer was hurt when the crowd pushed forward. I observed a protestor who had been hit in the head with a bottle or maybe a bean bag. It was unclear. A group, all women, most of them Black, gathered around the injured white man, giving him bandanas to help stop the bleeding. He eventually wandered off, refusing help from an APD officer who approached him, and continued up the frontage road.

As the night wore on, more bottles were thrown, more shots were fired. The crowd pushed forward, police pushed back. The helicopter continued to circle until well past 2 am.

If this was the opening act, Austin was in for a long weekend.

Saturday

The helicopter took off again on Saturday morning, reigniting its incessant hum. Protests, we learned, had continued all night. What started in Minneapolis had spread across the nation, popping up in every major city, including San Antonio, Houston, and Dallas.

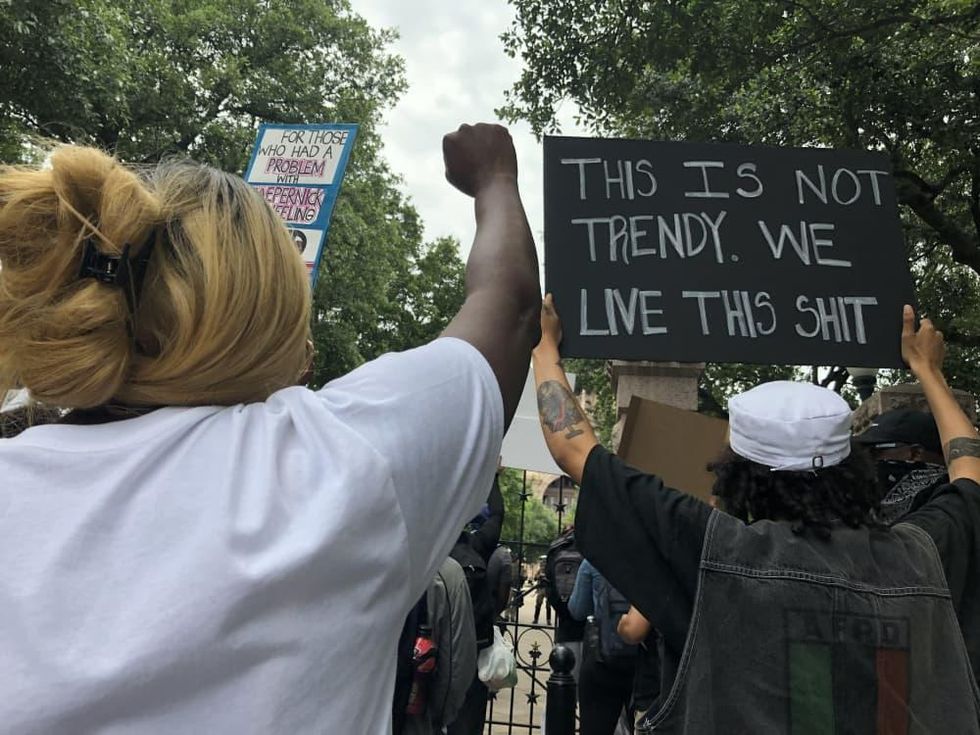

By noon, hundreds more protestors were back downtown, mostly peaceful, yet defiant. They gathered at Austin City Hall, the Texas State Capitol, and APD headquarters, bringing more young people, more signs, more snacks, more free water bottles and granola bars, more street medics, and more gallons of milk.

Billie, a mother of five children — all boys — had brought her three youngest sons to protest. The family stood on the sidewalk across from APD headquarters. Each boy, Michael, Anthony, and Donald, held a sign saying, "My life matters," while their mother stood in the middle clutching one that read: "Their lives matters."

The family moved to Austin about 18 months ago from St. Louis, where they participated in what is now called the Ferguson Unrest. Billie said it was wrenching watching the video of George Floyd's murder and hearing him call out for his momma while a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck.

"I want [my sons] to be respected," she said behind her protective face mask, "as Americans and men."

By early afternoon, most of the demonstrators gathered again in front of APD, some eventually climbing the steep cement retaining wall and onto I-35, bringing traffic to a standstill for nearly an hour.

It's hard to not look for the metaphor here. After all, I-35 is a highway that begins in northern Minnesota, runs through Minneapolis, cuts across the middle of the country, and heads south through Austin before it eventually ends at the Mexican border.

It is a symbol of American ingenuity, of connection and of commerce. In Austin, it's also a symbol of racial divide and a constant reminder of the city's (often still) segregated past. When construction of I-35 began in the 1950s, the city pushed people of color to the east side of the highway, often cutting off city services if they remained on the west side of town. Today, it is a symbol of gentrification and a reminder that Austin remains the only major U.S. city to lose its Black population in spite of record-breaking growth.

Again, was anyone thinking of this when they hurried up the incline and onto the highway overpass? Probably not. It's easy to argue that it was just a coincidence, that I-35 just happens to run alongside APD headquarters. But that this site was chosen to house Austin's police force, a site situated on the west side of the highway, but with its imposing facade positioned to face northeast? That's perhaps less coincidental.

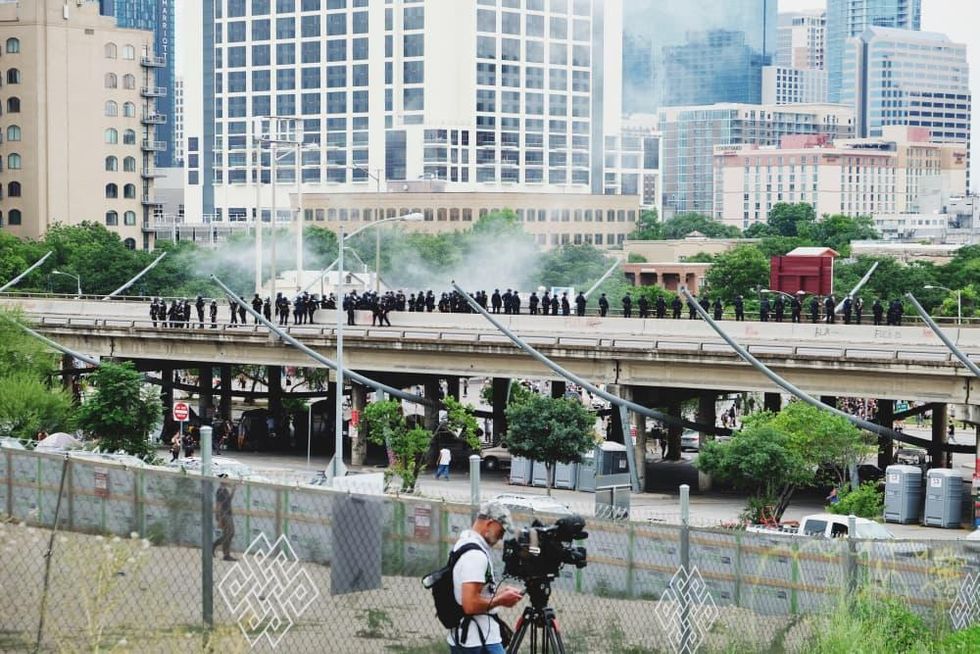

Police, some on horseback, some in cruisers, eventually dispersed the protestors using pepper spray and smoke. A line of officers took over the far right lane — the lane closest to APD's building — aiming their bean bag guns down upon the crowd that was once again gathering outside the front doors.

The crowd — and the officers above — would remain for the rest of the night.

Around 9 pm, the shift, the ground swell, the feeling that something, anything, had to happen, returned. By 9:30 pm, someone was jumping on top of a minivan parked under the overpass. Within minutes, the van was ablaze and smoke pooled under the concrete and through the homeless camp. One man sat on a couch next to his tent, watching the fire while another man hovered behind him like a barber, shaving the back of his head with a disposable razor.

Saturday night was when the looting began, spreading down Sixth Street and into liquor stores and other shops. Graffiti, most of it targeting APD, spread across downtown, reaching as far as the trendy South Congress tourist district. By Monday morning, we'd learn that 30 people were arrested. Among the charges were "burglary of buildings, interference with public duties, theft of property, theft of firearm, graffiti, engaging in organized crime, assault and participating in a riot."

Sunday

The helicopter was back by 10 am, making its same circular route around downtown in anticipation of an afternoon rally at the Capitol. The rally was in honor of Michael Ramos, the Austin man shot and killed by an APD officer after telling him he was unarmed, a fact later confirmed by police. Less than two hours before the 1 pm start time, it was called off by organizers at the Austin Justice Coalition over concerns that it would be hijacked by other groups.

"Over the past two or three days, it has been brought to our attention — and my attention — that ... a lot of other people of color, non-Black bodies, and white folks have co-opted and in a way colonized, like they do everything else, this particular moment," said AJC's executive director Chas Moore in a Facebook video. "White people have colonized Black anger and the Black movement in this particular timeframe and have used Black pain and Black outrage to just completely become anarchists."

"Here in Austin, if you look at what happened yesterday [Saturday], it was predominantly white people doing what they want to do," Moore continued.

We will likely never know the exact demographics of the protest, but it's likely they echoed that of the city, which skews young and white.

Despite the cancellation, thousands of protestors still showed up, first at Austin City Hall where they were met with pepper spray and rubber bullets, then at the Capitol where they were met with locked gates and armed officers from the Texas Department of Public Safety.

"This is for Mark Ramos!" shouted one white woman. As I turned to look, certain I had misheard her, the woman repeated her mistake. "This is for Mark Ramos!" she screamed again, punching her fist in the air.

By 2:30 pm, the crowd circled back to the headquarters and back onto I-35, once again bringing traffic to a standstill.

"I didn't know Austin had that many police officers," one young Black protestor mused as she looked down at APD headquarters from the southbound lane of I-35. It seemed that nearly all 2,100 of the city's uniformed police were there — all of whom had been recently told they would pulling 12-hour shifts for the "foreseeable future."

As more people streamed onto the highway, some using the barricade between the south and northbound lanes as a tightrope, the helicopter circled above, ordering the protestors to move. When they didn't, the helicopter threatened to use non-lethal force. People remained. After a final warning from the helicopter, officers appeared with military like precision, deploying canisters of crippling tear gas and smoke. Plume after plume wafted down the highway and settled onto the street below. In the moments that followed, APD would tweet to media that it had not used tear gas only to retract that statement after multiple journalists reported it was untrue.

"This is a fluid situation where the safety of the community is always our priority," APD said in its retraction. "Smoke and CS gas was deployed to move crowds off of IH-35."

As Sunday came to a close, looting continued, including a Shell station and World Liquor on East Sixth Street. Burglaries were also reported at a Target in Capital Plaza, more than four miles away from the epicenter.

When historians look back at this weekend, they will inevitably tie it to the novel coronavirus. The same week America hits 100,000 deaths from COVID-19 — a virus that disproportionately affected Black communities in both deaths and economic fallout — the country burns. A people taunted by their own president ("weak" Trump called state governors after spending part of his weekend hiding in a bunker) took to the streets and raged. A nation shutdown by a global pandemic emerged for a single weekend to commune in anger.

But was that anger spurred by the past 12 weeks of inconvenience or the past 400 years of injustice? Perhaps that too will be left to the historians to decide.