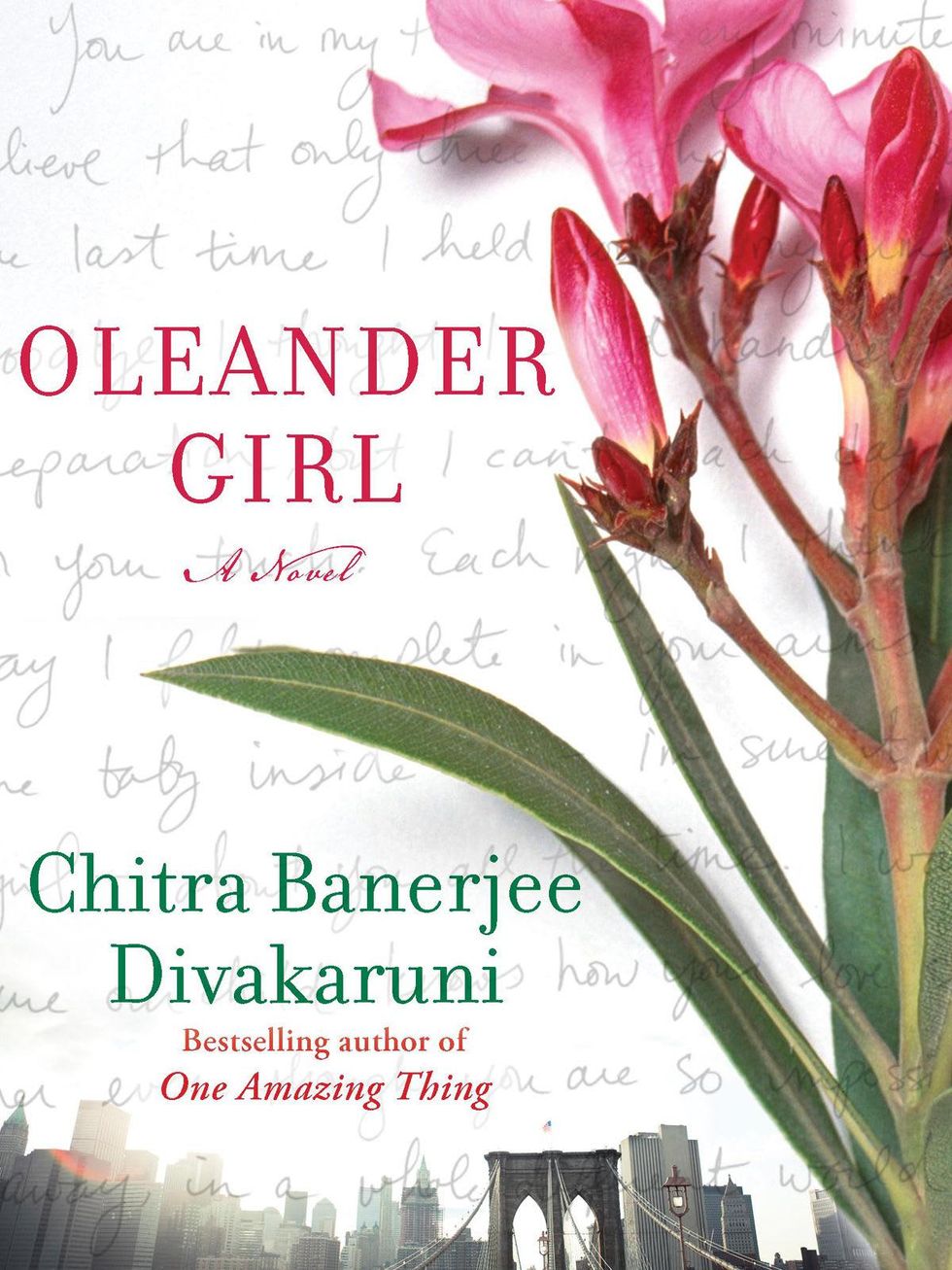

In Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni's new novel, Oleander Girl, a young Indian woman's engagement ceremony is shattered when the grandfather who raised her falls mortally ill. With this tragedy, family secrets and lies are suddenly revealed, and she soon discovers that she is not the person she always believed herself to be. Only in the United States can she find the truth about her identity.

Before embarking on a multi-city reading tour, Divakaruni, the award-winning novelist and University of Houston professor, answered some burning questions for CultureMap. Divakaruni will be speaking and holding a book signing at Book People on April 17.

CultureMap: You dedicated Oleander Girl to your grandfather, with the note that his life inspired the story. Can you talk about that?

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni: I wanted to write about family secrets. I wanted to write about the clashes between the old and new in India. As I was writing, I realized something like this happened in my own family, with my own grandfather.

I had pushed it into my subconscious, because it wasn't something I was happy about. My grandfather was a wonderful man, as far as I was concerned. He was very nice to me always. But as I grew up, I found out he had been quite harsh to his own children. He had disinherited a couple of my uncles.

I realized that the grandfather in this book was based on my own grandfather, to some extent. I hadn't realized that until I was well into the book, and so then I thought: I want to dedicate this to him.

CM: In a previous interview with CultureMap, you described how your novel One Amazing Thing was inspired by your family's experience fleeing Houston during Hurricane Rita. Do you often use your own life experiences as inspiration but then transform those experiences into something new in a novel?

CBD: Yes, I think you're right. There will be something in my life, like with One Amazing Thing — and, in this book, my grandfather — but once I start writing, that goes away and I enter the world of imagination. That space is so much larger, and anything can happen.

If I stay close to my life, then I'm constricted by my life. If I can use whatever was in my life as a bridge to enter the world of imagination, then a book can take off and do whatever it needs to do.

CM: Something unusual about Oleander Girl is that about half of the book is told in first person with Korobi as the narrator, but then the other half is told in third person. What were you trying to achieve by mixing narrators?

CBD: I've always been interested in perspective and points of view. What's so interesting in a story is that the same event appears so different to different people.

A lot of these characters in Oleander Girl just don't see life the same way, and that causes a lot of conflict. But I felt this was really Korobi's story. She is the one discovering things more than anyone else. On one level it's a coming-of-age novel, so I wanted to show her point of view most closely.

CM: In many ways, Korobi's story follows Joseph Campbell's hero's journey model.

CBD: Yes, I love Campbell. I've read him over and over. It's really the hero's journey. She gets a call to adventure. It turns her life upside down. She has to make a decision. She had to leave the familiar world.

CM: Which brings us to the question of setting. Korobi leaves the familiar world of India to venture into the strange, alien world of New York City about a year after 9/11. Why was it important to set the novel in that time?

CBD: I wanted to look, not at the immediate effects [of 9/11], but the other effects that have continued to accrue. How have people's lives changed after the immediate shock of the event?

That's a major theme in Oleander Girl. How do we live together in a world of difference? How do we live together when things like religion and ideology are driving us apart? And I wanted to show that going on both in India and the U.S. In India that's the year of the Gujarat riots, the terrible Hindu/Muslim riots that caused a lot of devastation all over the country.

CM: Did you find that there was any element in the novel that was a departure from some of your previous work?

CBD: One of the things that really interested me in this book is how the action splits. Korobi goes to the U.S., and her fiancé stays in India. Now the action has split, so the challenge then is how is the action going to come back together.

CM: There are points in the novel when Korobi calls home to talk to Rajat, her fiancé, and they still seem to have a strong connection, but it's like they are in two different worlds and talking around each other.

CBD: That's a phenomenon I've experienced. When you're in India and when someone you love a lot is somewhere else, maybe in the United States, it's like you're in different worlds. What's important to you is so far away from them.

I know this because my mother and I would have conversations, and of course I was concerned about her life. But I couldn't really feel what was going on in her life, and she couldn't feel what was going on in mine, even though we loved each other. That was what I was trying to convey.

I hope to show how difficult it is for people who are living in different parts of the world, how difficult it is to communicate. The psychic distance is still a big deal. Even in this time of the internet, miscommunications happen. Distances are created. The human psyche is just a strange animal.

Novelist Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni is a professor at the University of Houston.

Photo by Murthy Divakaruni

Novelist Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni is a professor at the University of Houston.