Homeless Cry for Help

Want to get bummed out? Read one homeless woman's manifesto graffitied on new East Side condos

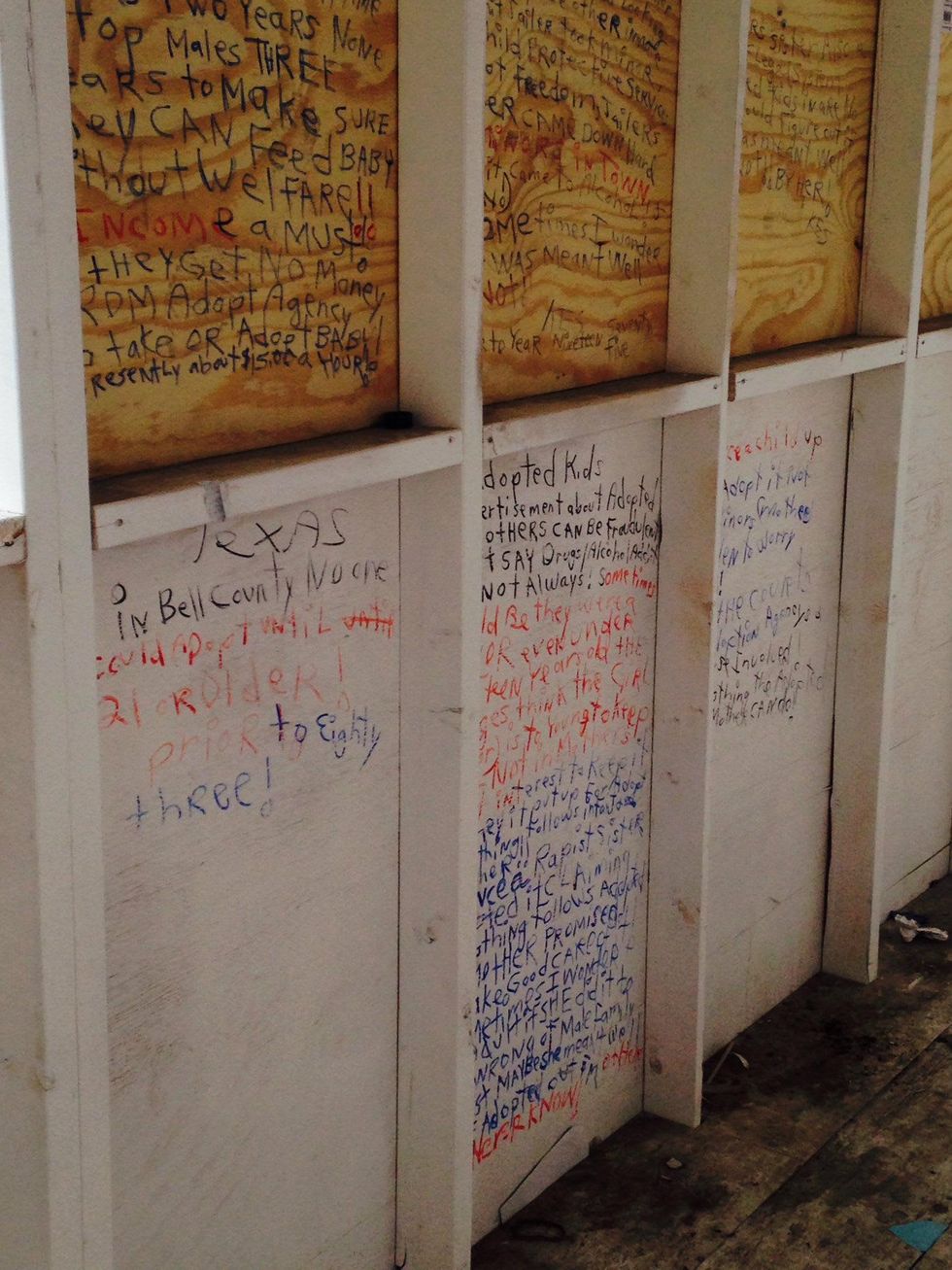

In alternating black, red and blue marker, running the length of an entire city block, a pedestrian tunnel on East Sixth Street in East Austin has been transformed from a construction barrier into one woman's manifesto on poverty, mental illness and homelessness.

The tunnel, a white-washed wooden protective barrier installed along East Sixth Street between San Marcos and Medina Streets, was branded in part as a public arts space while construction on a 17,000-square-foot luxury apartment building, called the Corazon, is under way. Partnering with local street art collective Spratx, Corazon asked artists to design wooden hearts to be hung the length of the walkway. Though it is unclear what the original intention for the interior of the walkway was (calls to Corazon's management company, Greystone, for clarification went unreturned), one woman has turned dozens of panels into an outlet for outrage.

Consisting of thousands of words, Sackett's graffiti paints a portrait of one Austin woman's struggle with poverty and mental illness.

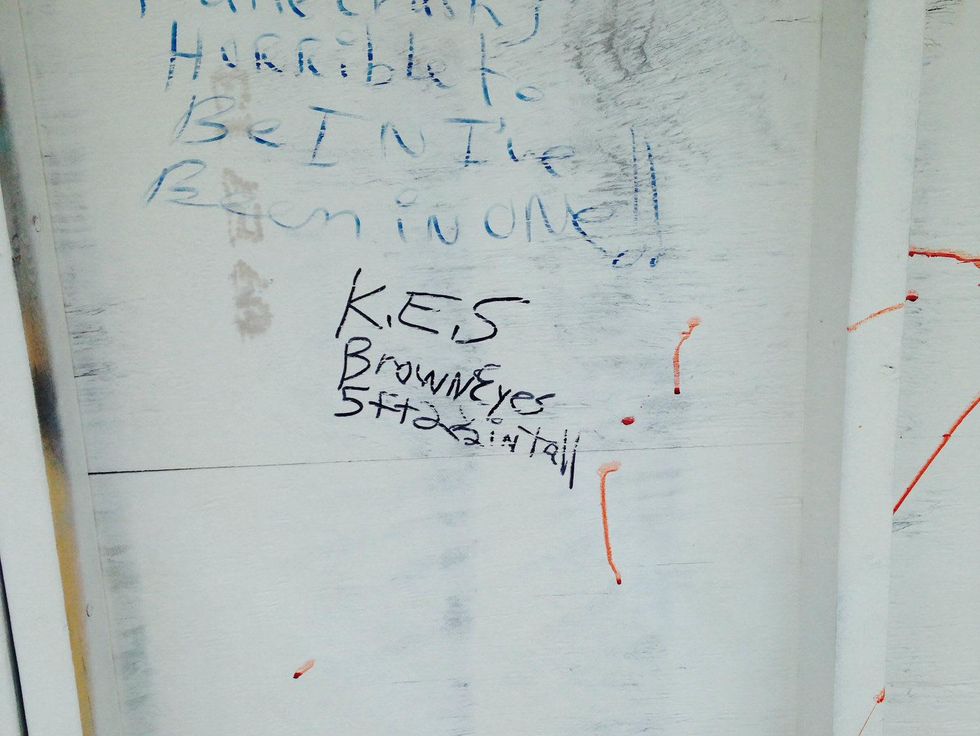

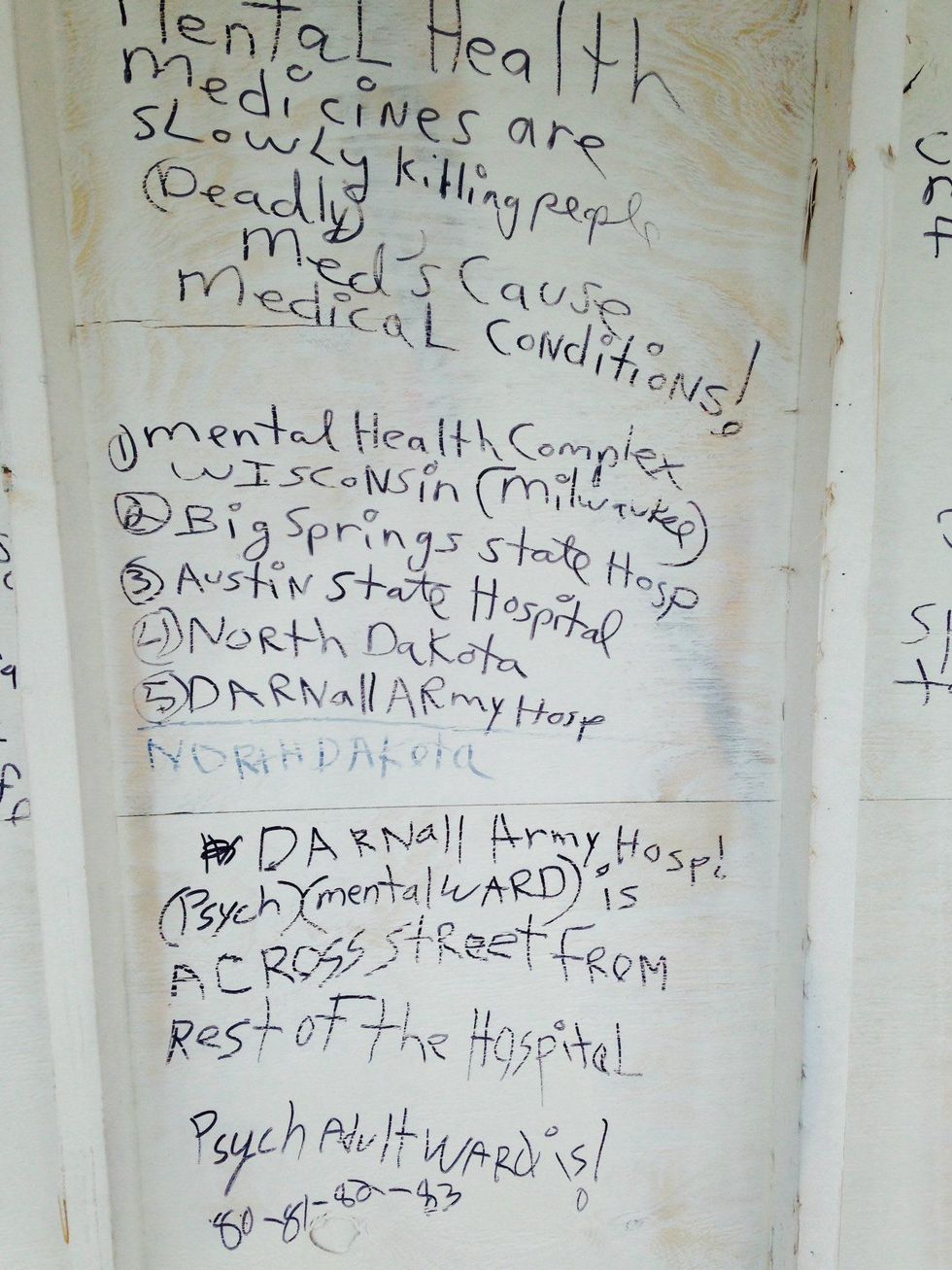

In a style that calls to mind a series of Yelp reviews, the writer, who identifies herself as Katrine Elizabeth Sackett, lists her height (5 feet, 2 inches), eye color (brown) and date of birth (March 24, 1963) while painting a portrait of her life: born in the Midwest, she claims to have spent time in the Army and details a miscarriage she suffered before listing five mental hospitals where the writer says she received treatment.

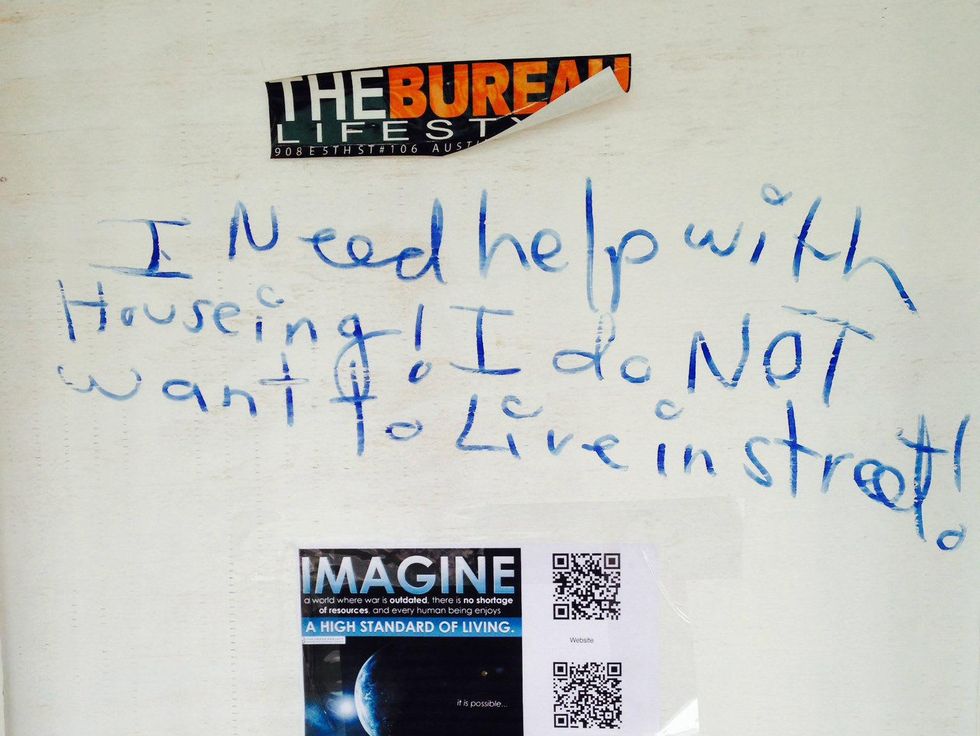

In between these details, she crafts weird (and sometimes cruel) diatribes attacking everything from the U.S. military ("You taught me little to nothing") to local homeless advocacy group ARCH ("Someone stole my clothes while in the shower"). At times funny (she refers to President Barack Obama with the Irish-inspired surname "O'Bama" and claims Supercuts gave her a bad trim) and other times nonsensical and downright racist, her diatribes have turned the site of Austin's newest condos into a portrait of one woman's battle with mental illness and homelessness in our city. "I need help with houseing! [sic] I do not want to live in the street!" she scribbles.

Sackett is not alone. In 2013, more than 14,000 Austinites received help from Austin's various homeless services systems, according to the Ending Community Homelessness Coalition. More than 2,000 of those folks are living on the streets.

Consisting of thousands of words, Sackett's graffiti is both enlightening and deeply disturbing; her words highlight an issue that is often riddled with bias — if it's ever discussed at all. It is estimated that about a quarter of the homeless population in the United States suffers from a "severe mental illness." (By comparison, only about 6 percent of the nonhomeless population is classified as severely mentally ill.)

While developers might be addressing Austin's housing shortage via luxury apartments for the 115 or so people that move here every day, Austin advocacy groups are continuing in the fight against homelessness and address untreated mental illness. "Austin has such an incredible shortage of affordable housing for any population," explains Jo Kathryn Quinn, executive director of Caritas of Austin. "It's extremely scarce for the chronically homeless."

There is no shortage of studies that equate stable housing with everything from longer life span to higher self-esteem, but Quinn says that it's the critical component for people looking to break the cycle of poverty. "People cannot solve the issues that landed them on the street until they're off the street. Until they solve the issue, mental illness, substance abuse or plain ol' bad luck, it's almost impossible to get a job while you're still living on the street."

As a city, Austin is making some strides to make affordable housing available. In November, voters passed the 2013 Affordable Housing Bond, a $65 million dollar bond (to be paid via property taxes) to provide "affordable rental and ownership housing as well as for the preservation of existing affordable housing," according to the city of Austin.

Like most major American cities, Austin's homeless population has remained relatively stable over the past five years, following decades of increase.

But while the city may be making strides, the Austin Police Department — especially the chief of police — is making headlines for wanting the homeless gone. In 2012, Austin Police Chief Art Acevedo made headlines after stating publicly that he wanted to move Austin's homeless organizations out of downtown. Noting access to alcohol and interacting with police as the two key issues, Acevedo said, "Let's put Caritas, let's put the ARCH, let's put the Salvation Army right adjacent to this huge district. It has beer readily available and booze readily available; it's probably not a good mixture."

Acevedo made headlines again in September when he was supposedly attacked by Michael Fitzsimmons. Fitzsimmons, who is homeless, allegedly tried to kick and punch the chief (who was in plain clothes at the time) after Acevedo asked him to leave a restaurant he was patronizing. The media outrage was swift, with one local news outlet calling the incident the latest in an epidemic of "homeless aggression."

This isn't a situation unique to Austin, according to Quinn. "[The homeless] population typically ... just by virtue of living on the street, they have more exposure to law enforcement. It's like it's a crime to be homeless — urinating in public, public intoxication, violating quality of life ordinances."

Quinn continues, "And there's a lot of stigma. People automatically assume that they're dangerous. What the data proves is that [the homeless population] does not have higher instances of violence; what they have is that they get offenses because they are homeless."

But despite bouts of negative publicity over the past few years, Austin is seeing some improvement. Like most major American cities, Austin's homeless population has remained relatively stable over the past five years, following decades of increase.

In order to keep this stability (and begin seeing improvement), Austin must keep battling for affordable housing, not only for our homeless citizens, but for the creative class that has proved integral in shaping our cultural identity. It's a sentiment echoed by Quinn. "Once you get into housing," she says, "the sky's the limit."

Lots of people want to live in Leander. Leander Parks & Recreation/Facebook

Lots of people want to live in Leander. Leander Parks & Recreation/Facebook