Museum Beat

Austin museum's latest exhibition is a look at America's turbulent past

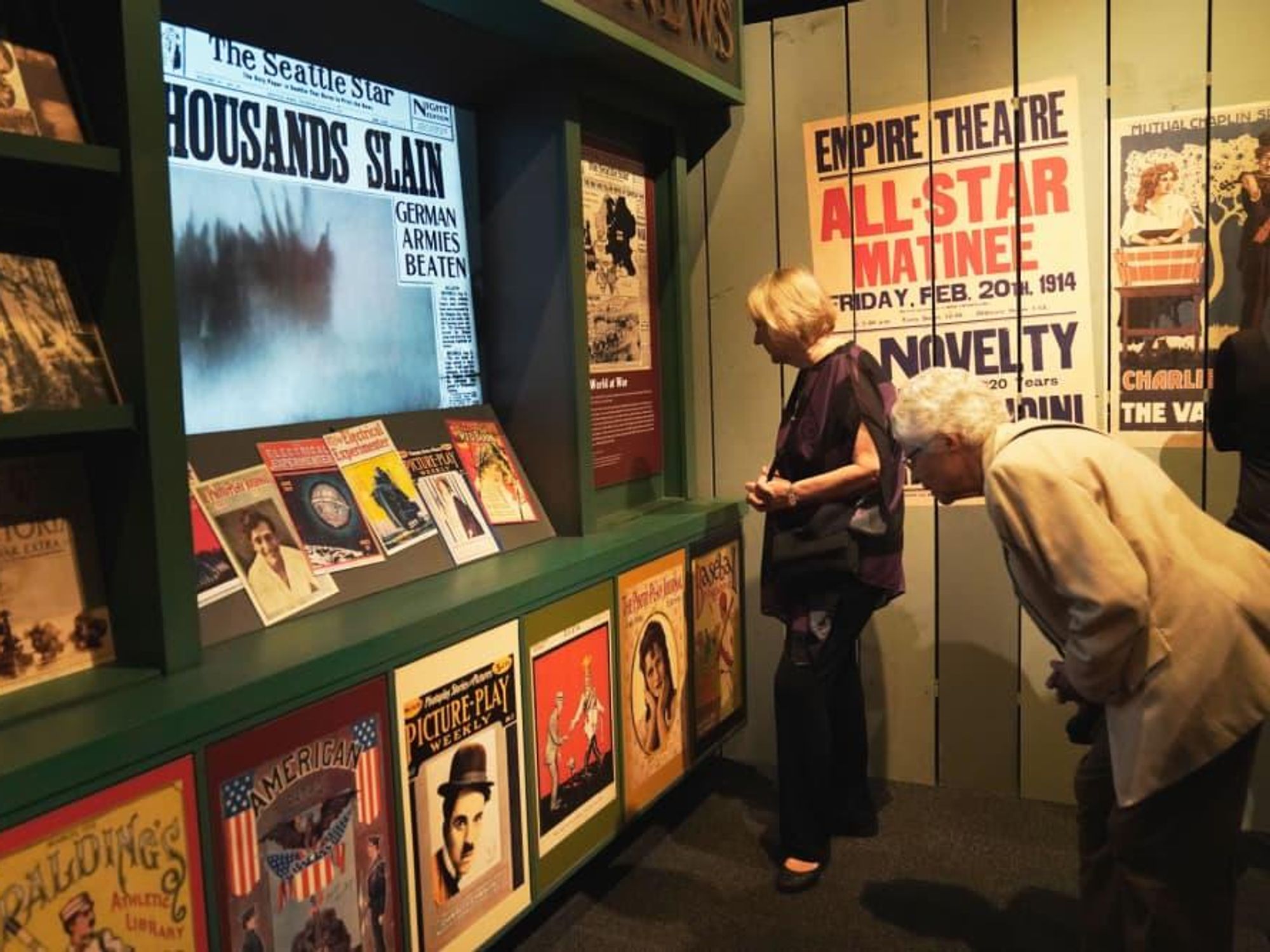

“Must children die and mothers plead in vain? Buy more Liberty Bonds!” extolls a poster in the "WWI America: Stories From a Turbulent Nation" showing now through August 11 at the Bullock Texas State History Museum.

The patriotic advertising, aka propaganda, repeatedly leaps out from among a collection of equally bold and artfully drawn posters for the government bonds that sought to raise public money to help finance the war effort when America finally entered the war in April 1917.

Close to the posters is a mock-up cinema showing the silent comedies of Charlie Chaplain, whose physical antics and bowler hat made him a worldwide icon in early twentieth century cinema. Across from that is a full-size mock-up WWI army ambulance where video recollections of six Americans who participated in the war are projected inside.

“There have been a number of exhibitions that celebrated America's efforts in World War I from a military angle, [but] this exhibition is different,” says Kate Betz, the museum’s deputy director of interpretation. “It takes a deep look at what taking part in WWI did to America as a nation, pulling us away from isolationism and toward the modern nation that we know today. This point is made over and over through the stories and artifacts of relatable people, both famous and average citizens, as well as through interactive experiences to help connect visitors to a pivotal time period in our nation's history.”

Those average citizens highlighted in the exhibit include the likes of the 2 million “doughboys that set sail for Europe with the American Expeditionary Force." Doughboys was the nickname for U.S soldiers that came from when American troops fought in the Mexican-American War in the 1840s.

During that war, the infantry’s uniforms got covered in the white dust of the adobe soil of the Rio Grande region, leading to mounted troops calling them “adobes,” which soon turned into “dobies” and eventually into “doughboys.”

There were also the suffragettes fighting for women’s right to vote, and the immigrants flocking to America between 1900 and 1920 at the highest rate since the country’s formation.

The more famous faces featured include Madam C. J. Walker, the African American entrepreneur who is widely acknowledged as the nation’s first female self-made millionaire; Mary Pickford, Hollywood’s biggest star by 1917 and known as “America’s Sweetheart, who threw herself into promoting the sale of war bonds; Billy Sunday, the fire-and-brimstone evangelical preacher who used his sermons to attack the Kaiser and his “ghastly, hideous, infernal Prussian militarism.”

And of course, there’s Charlie Chaplain.

“I had no idea he was so funny,” says 15-year-old Santiago Asuege, visiting with his mom. “I had never seen him before.”

Any exhibition about World War I will clearly have a more serious side, but rather than focusing on the terrors of trench warfare, the show gives equal billing, if not more, to the tumultuous events happening back in America at the time.

In the immediate wake of the war’s end, it seemed to many that America was coming apart at the seams. The year 1919 was wracked by strikes, anarchist bombings, increased government repression of political dissenters, and widespread racial violence and race riots, during a period known as the Red Summer, when at least 26 American cities descended into horrific violence.

At the same time, an outbreak of influenza was killing hundreds of thousands in the U.S. — and millions worldwide — as old empires were crumbling, Communism was gaining a foothold, there were disastrous realignments in the Middle East and Africa, and the beginning of Prohibition a few months after America entered the war meant there was a national ban on the sale of alcoholic beverages.

“If we've done our job right as a museum, we present information in the form of artifacts, stories, and interactions in a compelling way that creates opportunities for our visitors to make their own connections to contemporary life,” Betz says.

But it was a very different world back then, though perhaps not so different.

Also examined in the exhibition is the idea that when fighting broke out in Europe in 1914, most Americans believed that the war had nothing to do with them, resulting in a significant peace movement across all swaths of societies.

But as the war raged on, questions about a possible, maybe even inevitable, role for America persisted. How could America stay out of a conflict that appeared to threaten to become the first “world war”?

Now, America has the most powerful military the world has ever known. But the same questions persist about the rights and wrongs of the country's interventionism in foreign affairs, and whether the country should get involved in other people's wars and in helping secure worldwide peace.

“We know many lessons can be learned by a more thorough understanding of the true complexities of history and hope that conversations are sparked after visits that will bring greater clarity to questions like this,” Betz says. “When the museum is planning our special exhibition schedule, we are always working to find a balance between scholarly and fun, with a mix of topics and experiences to ensure that the amazing complexities and richness of Texas's history, both good and bad, are brought front and center.

If you go to the Bullock Museum, give yourself plenty of time. There is much else to see, including another new exhibition called "Cowboys in Space and Fantastic Worlds," which makes for an interesting contrast to say the least.