rare birds

A Holden Caulfield Christmas: Why The Catcher In The Rye is the best holidaybook ever

I have never presumed that what I write has any influence on any single person whatsoever beyond a much-appreciated Facebook “likes” and Twitter “tweets.” But I hope that this week's column will inspire someone out there in Internetland to go out, buy, and read my favorite holiday book, J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher In The Rye.

If you’re not familiar with the book, be warned that The Catcher In The Rye ain’t no A Christmas Carol. Published in 1951, Salinger’s novel holds the dubious honor of being one of the most challenged books in U.S. literature. Which means that even as recently as 2009, parents and school board members all over America have tried to restrict the book from being taught in the classroom.

This post World War II period piece set for the most part in New York City during Christmas time with a wealthy white kid as its protagonist was recently described by a school board member in South Carolina as a “filthy, filthy book” (that’s “filthy” times two).

But what is it about this novel that makes it so subversive?

If you’re not familiar with the book, be warned that The Catcher In The Rye ain’t no A Christmas Carol.

Catcher is written in the first person from the point of view of 16-year-old Holden Caulfield who, with zero self-censorship, recounts the events leading to his being hospitalized for an apparent nervous breakdown. Caulfield’s story begins shortly after being expelled from private school Pencey Prep. After a fist fight with his room mate, he decides to leave school ahead of Christmas vacation and, before going home to face his parents, go blow off some steam in New York City.

So the subject matter, failing school and not giving a damn and then taking an irresponsible walk on the wild side has probably unnerved many a parent over the years. The book also contains a lot of swearing. In fact, the profanity is relentless, though quite artfully written.

Opening the book a random page I counted eight expletives, which, times 214 pages, equals 1,712 uses of the words damn, goddamn, goddamned, hell, f---, and Chrissake, as well as milder perhaps less offensive words including puked, bastard, and flitty. Underage drinking, smoking, and pre-marital heavy necking, as well as painfully awkward encounter with a prostitute and violent altercation with her pimp are all a part of the hero’s journey chronicled in the novel.

And indeed, the book is a journey, in the mythological sense of the word. However, how exactly Salinger's anti-hero is ultimately transformed at the journey's end is still a heavily debated subject. And personally, I think this speaks to the brilliance and timelessness of the book. It’s a novel that will resonate with you in different and new ways every time you read it.

A book worth rereading

When, I first read it, back when I was a teenager, my father who was a fan of the book told me that I should read it again in a few years and then a few years after that. He explained that over time the book would speak to me in different ways. Since then, I’ve reread the book every two years or so, and you know what? The old man was right.

As an adolescent, I was excited and empowered by the honest disgust Caulfield expresses when it came to “phonies” and anyone or anything that was hypocritical and untrue. Plus the smoking, the drinking? A hooker in a hotel room? Let’s be honest, I found all of that fascinating as well.

I reread the book years later, married and living in New York City, and was then particularly moved by passages where Caulfield describes the passing of his beloved younger brother Allie. I felt an almost paternal compassion for this fictional brat, as it was clear to me he lacked any adult guidance as to how to come to terms with such a tragedy.

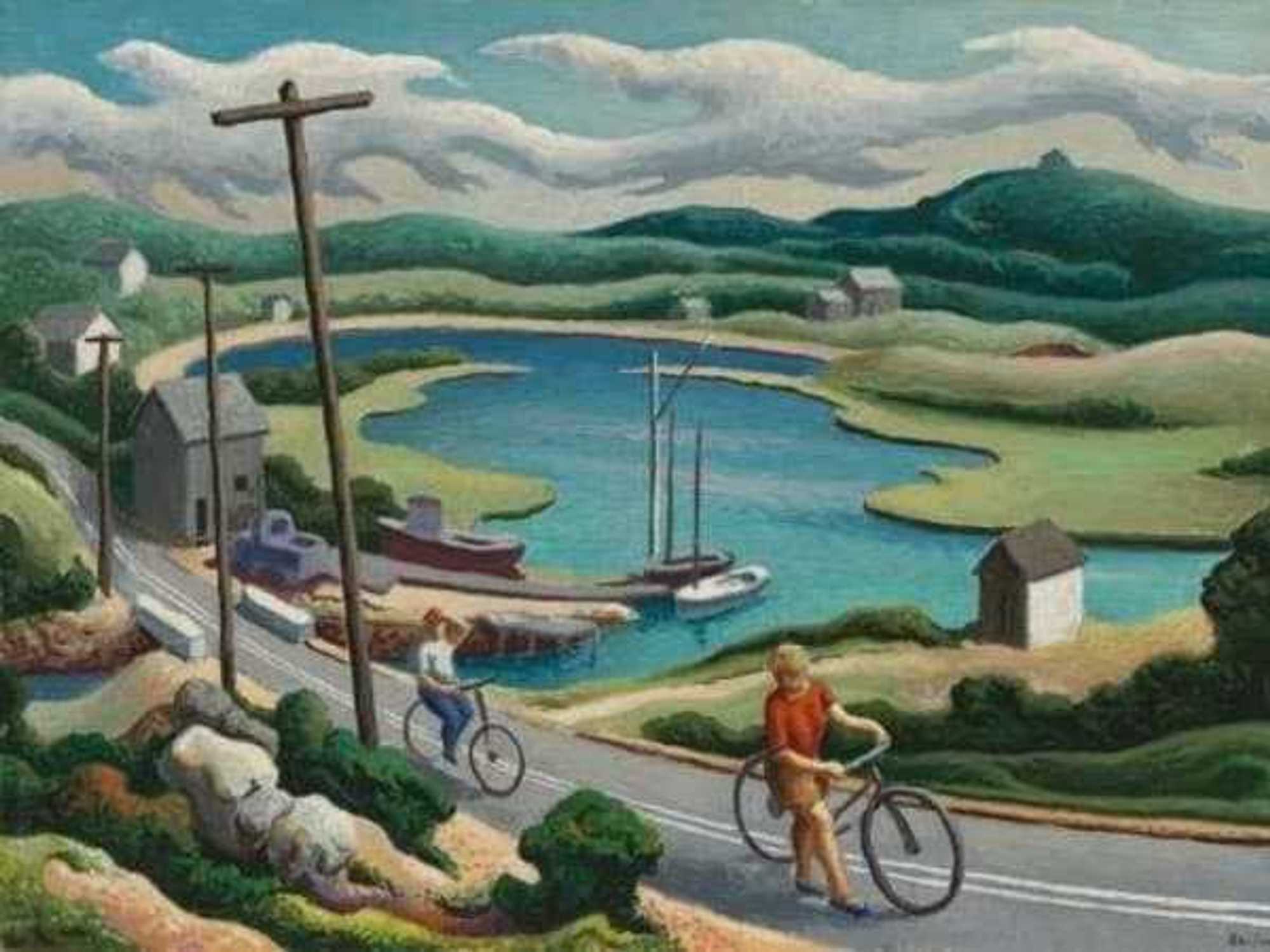

The specter of death is present throughout the book. Even Caulfield’s recurring obsession with the wintery fate of the ducks living in Central Park South’s lagoon speaks to the subject. During one of many cab rides, Caulfield brings the topic up with his driver, asking him how the ducks survive the winter freeze ("Does someone come around in a truck or something and take them away?").

The cabbie nearly causes a wreck in his passion to explain the mystery. “They live right in the goddam ice,” he yells at Caulfield. “That’s their nature, for Chrissake.”

Strangely, the cab driver's response prompts Caulfield to ask, “Would you care to stop off and have a drink with me somewhere?” You can just feel the cabbie thinking, “Who is this f---ing kid in my cab?”

Speaking as a now middle-aged fan of the book, I feel a great empathy towards Caulfield whose only wish is to somehow "catch" children in their innocence and protect them from falling into the abyss of the unknown. But I feel less for the children and more for the young man overwhelmed in his journey to adulthood.