92 Days of Summer

8 tips for teaching your kids to be citizens of the world

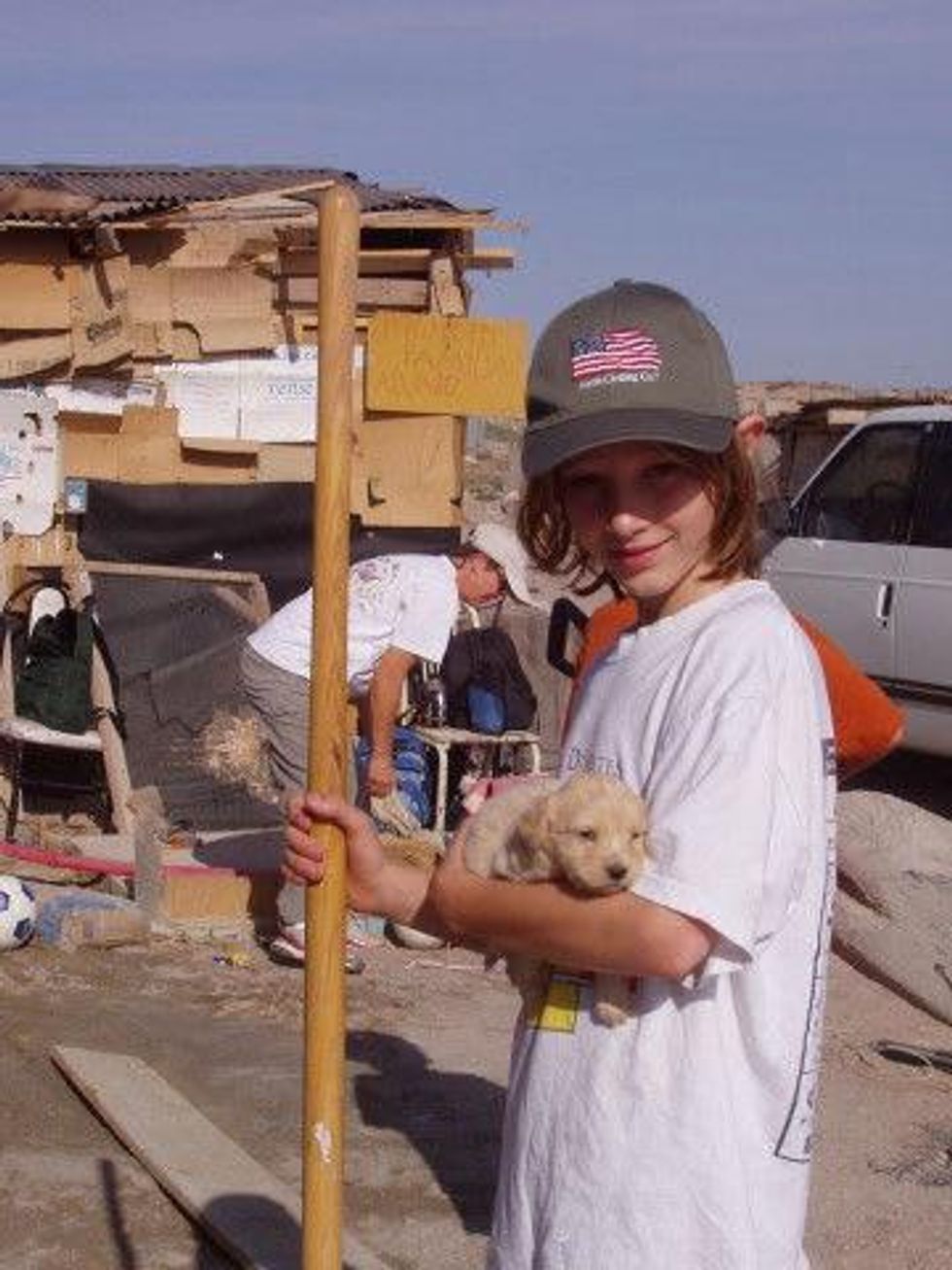

The first time we took our boys to Juarez, they were 5 and 8. We spent a week that summer and the next building houses for people who had been living in death traps, basically constructed from trash.

The second year we were there, we built next to one such house that had caught fire (makeshift electricity and trash structures don’t play well together), killing one of the family members.

Their young impressions of poverty in a third-world country?

- The local kids had an enviable amount of freedom. They ran around, unsupervised, playing soccer in the streets. This is not a freedom my children have living in urban Dallas.

- When you use the bathroom in an outhouse that has gaps in the wooden slats, you can pee and see chickens. At. The. Same. Time. (This actually was the perspective of another friend’s young son.)

- Grown men cry, whether they are on the giving or receiving end of a safely constructed house.

- A house of 288 square feet is enough.

- Stray dogs and puppies are plentiful.

- A child can mix concrete in the street. A child can organize school supplies. A child can play with another child with no common language. A child can.

Because of the drug violence, 2006 was the last time we took our kids to Juarez. Now, we sometimes send money, which is helpful yet not at all the same. But almost every summer, we try to do something that makes this world a better place and/or expands our children’s perspective from that of white, American and middle-class.

This summer, my older son turned 16 while building a Habitat for Humanity home in El Salvador. I am a proud momma, and he has done some impressive things (usually athletic) in his life. But I have never been more proud of him than I was that week.

Last summer, he and his dad went on the trip, so he knew the lay of the land. This time, he was the only teen to go, traveling with seven adults from our church. Both years, the team from Dallas and the locals he was building with commented on what an incredibly hard worker he was — an inspiration, they went so far as to say.

This is confidence in yourself you can’t get in many other situations: confidence in your body, in your personal ability to change things in our world, in your ability to take care of yourself (yes, he kept up with his passport the entire time and never drank water he shouldn’t have), and in your ability to function outside your comfort zone.

I have seen a grown woman break down and cry after a week in Rwanda because she was overwhelmed by third-world everything. I had done the same thing a few days before after children taught us how to work a rice field. This is not uncommon for those of us with first-world problems.

I am a big believer in letting children experience the world. And there is a lot of good in our world. But there is also much injustice. There is a world outside our 2,100-square-feet East Dallas home with the white picket fence, private school, private swim/tennis/rock climbing/guitar lessons, grandparents with unlimited soda, summer afternoons at the KC pool, movies at NorthPark, two-week road trips, and an iPhone in every stocking.

And, as we’ve tried to show them that world, here are a few things we learned along the way:

1. It’s okay if your kids are uncomfortable.

My youngest son was not happy at first when he found himself sitting in a Juarez classroom, surrounded by kids he didn’t know who spoke only Spanish — with whom he was expected to interact.

He was a thousand miles and cultures away from his comfort zone. I was patient for a while. I stayed with him for a while. I suggested activities he might do with the local kids for a while. Then I eventually left him to struggle through it. He did, and soon he was drawing and playing parachute in front of the one-room school.

This honestly may be the last time I remember him feeling that uncomfortable.

2. Get your kids away from their friends — and, eventually, away from you.

The older kids get, the less pleasant they are to be around when their friends are around. Alone, my 16-year-old is funny, intelligent, grounded and curious. Around his friends (at least some of them), he’s an asshole.

Yes, they slept on a concrete floor as “refugees” in Heifer Ranch’s Global Village and built a bridge across a pond at Morning Glory Ranch with some of their closest friends. And this was all good stuff.

But if you want to see your child, especially your teen, really open himself up to such an experience, separate him from his friends. And, when he’s old enough — which is probably before you are completely comfortable with it — from you as well.

3. At some point, let your kids find their own passion about how they can make a difference in the world.

I’m not talking about what you care about. I’m not talking about checking off a list of what looks good on the student resume (more on that shortly).

My 16-year-old has to fulfill a certain amount of community service for the International Baccalaureate program at Woodrow Wilson High School. Our conversation about his going to El Salvador earlier this summer had nothing to do with that. Our conversation about how he might build on his experiences there that to make a bigger difference — and meet his IB requirements — did.

It went something like this:

Me: “So let me just toss out some obvious stuff we’ve talked about before that you could do. Orphans in Africa? Are you interested in helping them? Homeless people? Something with the environment? Something with animals?”

To which my 16-year-old, unapologetically and repeatedly, answered no. To which I began mentally preparing for him to break my heart in two short years when he votes Republican.

Me: “How about the people in El Salvador you’ve built houses for. Are you interested in helping them?”

Him: “Yes.”

Done.

4. Don’t ever bring up that damned student resume.

Yes, my older son and I had a discussion about what would meet the requirements for the IB program at his school. Yes, he will put this on his college applications. But the discussion was never just about that. It was about what he cares about outside of him.

With all due respect to the selective high school/college game we are all expected to play, if what your child cares about is padding his resume, I suspect you have way more to worry about than what acceptance letters are coming in the mail.

5. Create a simple “this is what we do” environment.

Don’t pat yourself on the back. Don’t talk about “those poor people.” The world is unjust. Some people in this world need your help. Show your kids that they are not better than an orphan in Africa, a boy in Mississippi whose English is far from perfect, or a family cooking over an open fire in El Salvador by treating those people with respect.

Such people usually are happy, intelligent, loving, honorable and hard-working. I often see more smiles and gumption in poverty than I do in wealth. We are there to help and to learn. We are not there to push our ways and pity.

6. World-changing experiences do not require a passport.

In addition to helping out at the equine therapy ranch near Houston and learning about global poverty at Heifer, we have painted homes in South Dallas and hosted two teenagers from the Mississippi Delta. The latter was as big a culture lesson as any I’ve had that involved an international flight.

7. Be realistic about the danger.

And, in saying that, I mean don’t freak out. I am on the board of directors of a sewing school in the Democratic Republic of Congo. I will go there someday. Hopefully soon. I would probably not take my children there.

When the drug killings in Juarez were making international news, we stopped taking our kids there. Other people did — and they were fine. There is a travel warning for U.S. citizens traveling to El Salvador. There are men with machine guns around town and, once when I was there, on our actual Habitat site.

People also get malaria there. Yet some member of our family has been there every year of the past four.

Consider the current situation, as well as the groups you’re traveling with (in our case, our church and Habitat for Humanity). Take malaria meds. Shut your mouth when you shower. (This is fun to teach a kindergartner.)

Don’t be stupid, but don’t immediately disregard such an opportunity out of fear. Doing good in the world doesn’t usually happen in Highland Park.

8. Treat and treasure these experiences as you do all your other parenting best hits.

When you look over our summer photos or read my Facebook posts for these past three months, it certainly appears to be a child-focused, somewhat indulgent life my teen boys lead between the final exams and meet-the-teacher night.

I consider these moments right up there with seeing the Grand Canyon for the first time, snorkeling with a shark off Key West, sleepovers with dear friends, football games in the front yard, canoeing with the family dog, and getting your first car.

Maybe even better.

Shoppers browse local vendors and handmade goods during the Paper + Craft Pantry Lunar New Year Festival at Springdale General. Photo courtesy of Paper + Craft Pantry

Shoppers browse local vendors and handmade goods during the Paper + Craft Pantry Lunar New Year Festival at Springdale General. Photo courtesy of Paper + Craft Pantry Families explore food stalls, crafts, and pop-up booths throughout the daylong community festival in East Austin.Photo courtesy of Paper + Craft Pantry

Families explore food stalls, crafts, and pop-up booths throughout the daylong community festival in East Austin.Photo courtesy of Paper + Craft Pantry