History of Austin

Austin's original entertainment district has one wild history

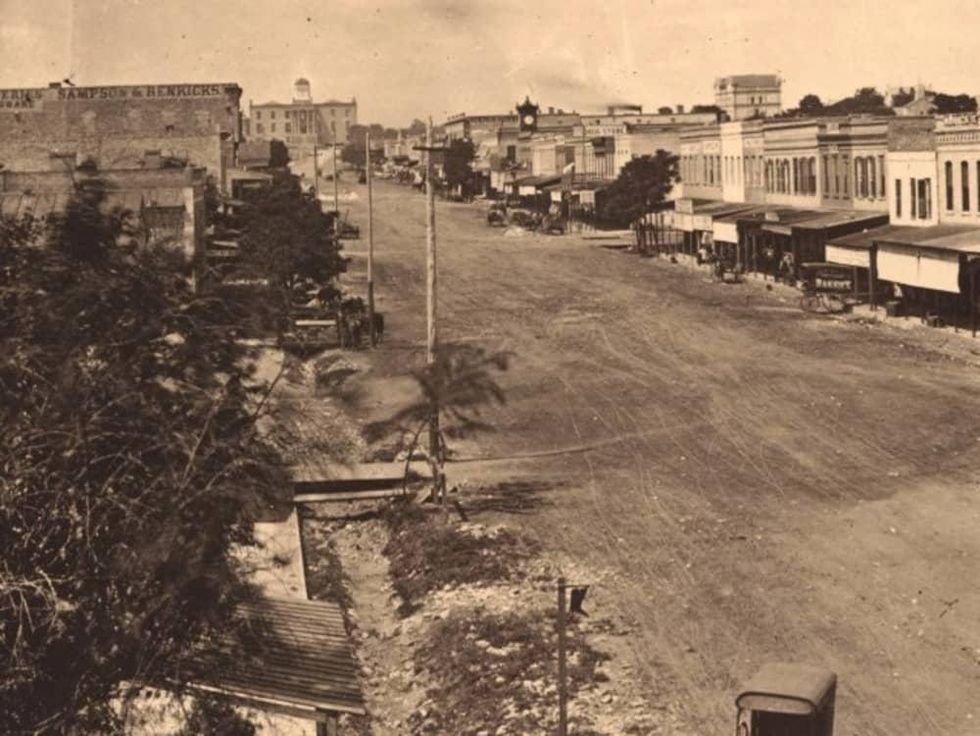

From 1870 to 1913, an inner-Austin, eight-block area bordered by Congress Avenue, the Colorado River, Guadalupe Street, and Fourth Street was brimming with brothels, saloons, and beer halls.

Austinites frequenting the area were arrested for such petty crimes as "rudely displaying a pistol" and "appearing in clothes not belonging to one's sex." The area was called the First Ward, and it began to be referred to as the jungles, or just Guy Town. At the same time, Austin grew from a population of 553 citizens in 1840 to 22,258 citizens in 1900.

During this period after the Civil War throughout the Lone Star State, other cities were experiencing forms of debauchery as well, from the Sporting District in San Antonio to the infamous Hell's Half Acre in Fort Worth and the vice districts in downtown Galveston and Houston.

Although Guy Town was mostly made up of financially-strapped residents, once businesses closed for the day, Guy Town came to life, with members representing all social classes flocking to the popular district. In fact, Texas lawmakers were frequent visitors to the bawdy area.

Cheap drinks began flowing from taps, chips were bet on gambling tables, and ladies of the evening were hitting the streets promoting their services.

Let there be light

In order to combat petty crime and properly illuminate the booming city of Austin, local politicians and community activists resolved to light up the night in hopes of eliminating sordid activities that previously took place when the sun went down.

The concept of moonlight towers was spreading across Europe and the United States; in 1894, the city bought 31 used moonlight towers from Detroit.

Austin is the only city in the world that still has historic moonlight towers. The remaining towers were noted by the Texas Historical Commission. One tower has a plaque reading: "This is one of the original 31 moonlight towers installed in Austin in 1895. Seventeen remain. Each tower illuminates a circle of 3,000 feet using carbon arc lamps (now mercury vapor). Austin's tower lights are the sole survivors of this once-popular ingenious lighting system."

Richard Zelade published the book Guy Town by Gaslight: A History of Vice in Austin's First Ward in 2014. What stood out for him while conducting research was the general "filthiness" that spread through the area.

"The gutters were filled with garbage," Zelade explains, "and the garbage was dumped into the river and Shoal Creek. It smelled to high heavens."

Visitors arriving in Austin at the train station on Congress Avenue at the western edge of Guy Town were appalled. Moreover, a powerful breeze traveling in the right direction would make for an unpleasant smell permeating the area.

All good things must come to an end

As the nation moved toward prohibition at the turn of the century, an increasing number of Austinites called for the demise of the First Ward. At one point the city council voted to close Guy Town, but the mayor overturned their ruling. However, as the music became a little softer and mayhem went on the decline, Austin police chief Will Morris declared a permanent end to the illustrious Guy Town in October 1915.

Very little of the original structures from Guy Town stand today. Only the old J. P. Schneider general mercantile trade store (built in 1873 and remodeled to become Lamberts Downtown Barbecue in 2006), The Market & Tap Room (a restaurant and event venue restored from the original building in the late 1800s), and Republic Square Park exist today.

Even as condos and commercial developments pop up in downtown Austin, the Warehouse District remains an entertainment destination for locals and tourists alike. From upscale seafood dining at Truluck's to Oil Can Harry's and Fado's Irish pub, you can find it all — including a colorful past — in this downtown neighborhood.