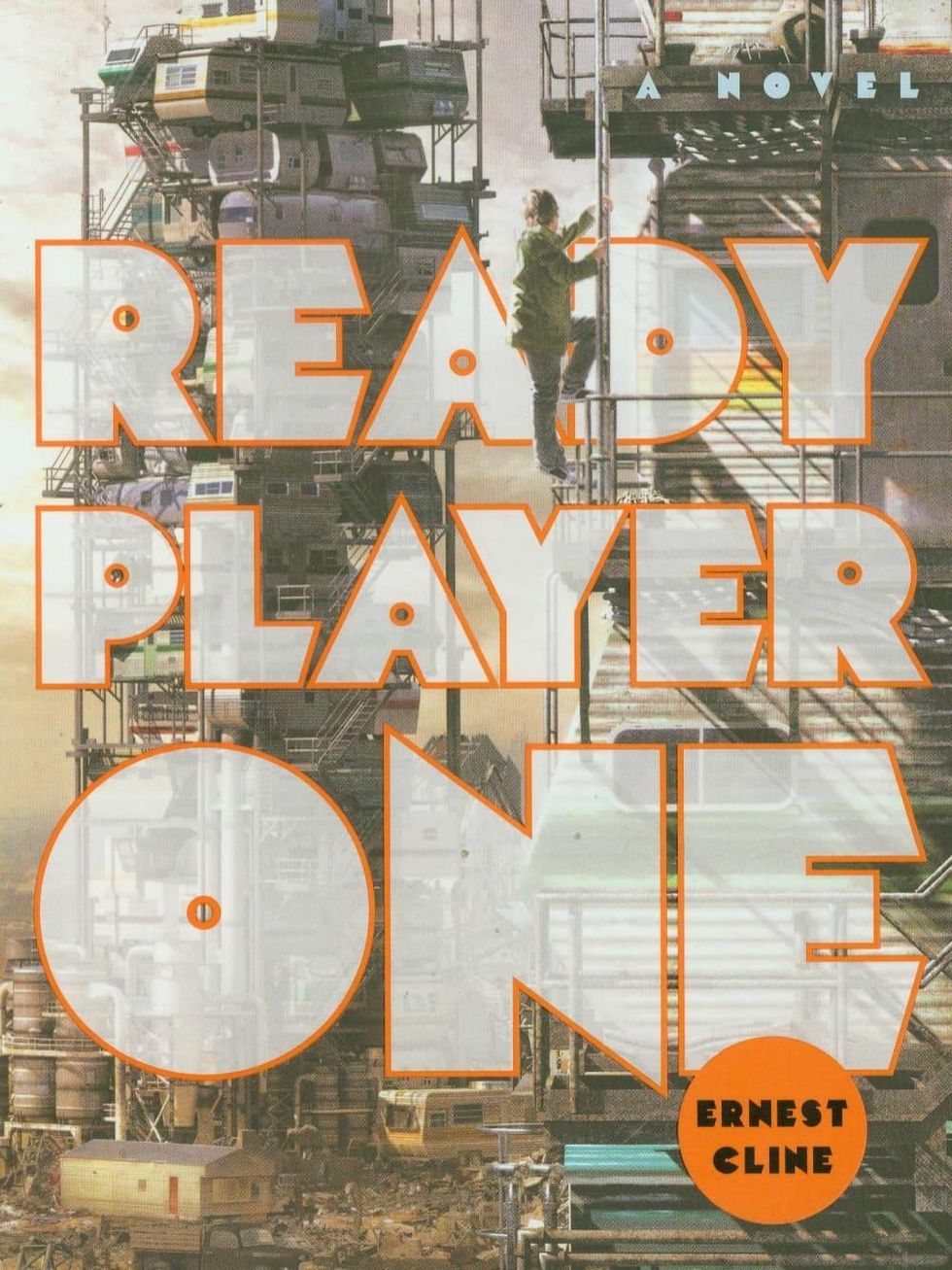

Ready Player One

Austin cult-classic novel lands huge movie deal with Steven Spielberg

Austin author Ernest "Ernie" Cline is living out every fanboy's ultimate dream. Not only did his breakout novel Ready Player One become a New York Times best seller, but that very same book is getting the royal film treatment by none other than Steven Spielberg, with a release date set for December 15, 2017.

The movie will be Spielberg's first directorial jaunt into science fiction territory since the fourth Indiana Jones installment in 2008. Ready Player One was originally published by Random House in 2011, but Warner Bros. snagged the movie rights before the novel even went to print (yes, it's that good).

As if Spielberg in the director's chair wasn't enough, the project has even more big names attached. Cline penned the original screenplay, but Zak Penn (whose writing credits include The Avengers and X-Men: The Last Stand) was tapped to assist with the movie adaptation. Rumor has it that Gene Wilder — most famous for playing the titular character in the 1971 movie Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory — might emerge from retirement for a role in the film.

For those who haven't read the book, the plot of Ready Player One is a total nerd-gasm. The story follows young Wade Watts in a not-so-distant dystopian future where society is obsessed with a virtual landscape called Oasis. When Watts joins an online competition with clues based on 1980s pop culture, the teenaged gamer explores how far he will go to win the billion-dollar prize — even if it means having to face the "real world."

Film reporters have been quick to note that with so many cultural allusions in the novel, Spielberg and his team may have a hard time nabbing the rights to make the same references in the movie. Ready Player One mentions everything from classic arcade games like Space Invaders to Spielberg's own Indiana Jones.

Cline's second novel, Armada, was just released to much anticipation in July, debuting at No. 4 on The New York Times' best-selling list. Reports say that not only are the movie rights to Armada already scooped up, but that Cline is also working on his third book.

A party can actually be together in the virtual world.Horizon of Khufu preview graphic

A party can actually be together in the virtual world.Horizon of Khufu preview graphic The experience doesn't just happen in the pyramid.Horizon of Khufu preview graphic

The experience doesn't just happen in the pyramid.Horizon of Khufu preview graphic The experience contains lots of cinematic shots.Horizon of Khufu preview graphic

The experience contains lots of cinematic shots.Horizon of Khufu preview graphic